The contest for precedence, or a turbulent day on London’s streets…

A long-lasting dispute over whether the Spanish ambassadors had precedence over the French, or the other way around, reached a bloody pinnacle on the streets of London on September 30 in 1661. On that very day the new Swedish ambassador was to arrive in London and according to custom, the King’s barge was to meet him at Gravesend and accompany him to Tower-Wharf. The destination being reached, the ambassador would be received in the King’s carriage and proceed to Whitehall with his own carriage following that of the King.

Behind the King’s carriage and that of the new ambassador, the carriages of all other ambassadors would line up and follow. In this case, both the Spanish and French ambassadors made it known that they desired the place straight behind the Swedish carriage. In past times situations like this had been solved by not inviting either of the parties, but in this case it was impossible. The ambassadors in questions were the Baron de Batteville for Spain and the Marquis d’Estrades for France.

In fear that the people of London might get involved, both ambassadors petitioned to Charles II, who at once issued a edict forbidding all Englishmen to get involved in the quarrel on the penalty of death. In turn, the Baron de Batteville and Marquis d’Estrades promised that no firearms would be carried be either side.

France and Spain both demanded the place of being the first, greatest and most powerful Kingdom of all of Europe for themselves, which was in this case dependant on the location of carriages. The outcome of this carriage-quarrel would later clearly define precedence, but not quite as the Spaniards imagined.

Louis XIV would not be Louis XIV if he would not have been somewhat involved in the matter as well. Already then, six years before the War of Devolution, he had an eye on the Spanish Netherlands and the vision that he should be the ruler of all of Europe. Thus it is likely that he provoked the events on September 30, on side of the French, to some degree.

The arrival of the Swedish ambassador was planned for three o’clock in the afternoon and Tower-Hill crowed with people. Almost all of London had come to witness the expected fray and almost all of London was on the side of the Spanish. As Samuel Pepys remarked charmingly “…we do naturally all love the Spanish, and hate the French.” Tower-Hill was not just filled with spectators, but also plenty of armed guards on foot and horseback in order to prevent the spectators from getting involved in the possible carnage.

The Spanish carriage got itself in an advantageous position by arriving five hours before the appointed time, much to the displeasure of the French, which arrived shortly after. Both carriages were accompanied by armed forced, the Spanish guarded by fifty men armed with swords, the French by one hundred men on foot and fifty on horseback. In contrary to what was promised, the French bore pistols and carbines.

As the appointed hour approached, the atmosphere got rather tense and as soon as the Swedish ambassador had placed himself in the King’s carriage and his own carriage had lined up, hell broke loose. The Spanish placed themselves on the road to bar the way for the French, which thus fired at them and chased them, swords in hand. Although they had the greater numbers, the Spanish managed to repulse them. Three horses, a postilion, and the French coachman were killed, but it had all just started.

The French carriage was manned by the son of the Marquis d’Estrades, who, severely wounded, leapt out of it and drew his sword to urge his fellow Frenchmen to do likewise. In vain. The Spanish carriage used the turmoil and distraction of the French to place itself behind that of the Swedish and was merry on its way already. But the French still had something up their sleeves. Armed men had been placed all over Tower-Hill and now launched another attack. They leapt to cut the traces of the carriage, but the Spanish were smart enough to use leather-covered iron traces. Obviously, they did not manage to cut through them and in turn were attacked by the Spaniards again. The latter won the fray and their carriage continued its way, half an hour later the French carriage followed with only two horses left.

The amount of casualties could not be calculated correctly, some speak of twelve killed and forty wounded, along with one dead Englishmen, a plasterer, killed by a stray French bullet to the head. (Samuel Pepys was present at the scene and wrote about in his diary on September 30 and October 4.)

As news reached Paris, Louis XIV was not amused at all… in public at least. The Spanish did exactly what he had expected, they insulted him and the Kingdom of France, and now he could do what he had planned. Louis dismissed the Spanish ambassador to France and recalled his own from Madrid, while letting it be known that he would declare war on Spain and annex the Spanish Netherlands should Spain not formally and publicly apologise to him. A quite brilliant win-win situation for Louis. Either Spain apologised, thus granting France formally precedence as Louis demanded “in all matters and all courts“, or he could snatch the Spanish Netherlands for France. Aware that Spain lacked troops to defend them properly.

Spain had no other choice but to go what in this situation was less harm to them and agreed to the Sun King’s demands. Half a year later, on March 24, 1662, the Marquis de Fuentes was sent from Spain to France, as an ambassador extraordinary, in order to apologise on behest of Spain and grant France precedence in all matters and in all courts over Spain. A spectacular reception was held for the occasion and twenty-six envoys from different European courts watched along with the Pope’s Nuncio as Louis XIV ordered all present ambassadors to spread the news.

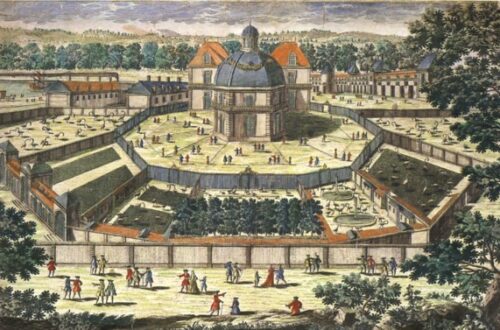

In order to make sure nobody forgot about it, Louis XIV commissioned a medal. One side showing his crowned head, the other how he kindly accepts the apology from a humble looking Marquis de Fuentes. The words “Praecedendi Assertum, Confitente Hispanorum Oratore” circle the scene and mean as much as the right of French precedence confirmed by Spain. Later the Royal Gobelin Manufactory created a large Gobelin of the scene as well.

One Comment

Adele

Oh my; this reminds me of school when everyone fought to be first in line.

Louis XIV was a smart manipulater; always planning ahead, and always had alternative plans.